A young and landlocked country, South Sudan is bordered by Ethiopia to the east, Kenya, Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo to the south, the Central African Republic to the west, and Sudan to the north. A long political instability coupled with geographic remoteness has resulted in an uncharted and largely unspoilt place — a fledgling country, which can genuinely lay claim to being home to one of the world’s last great wildernesses.

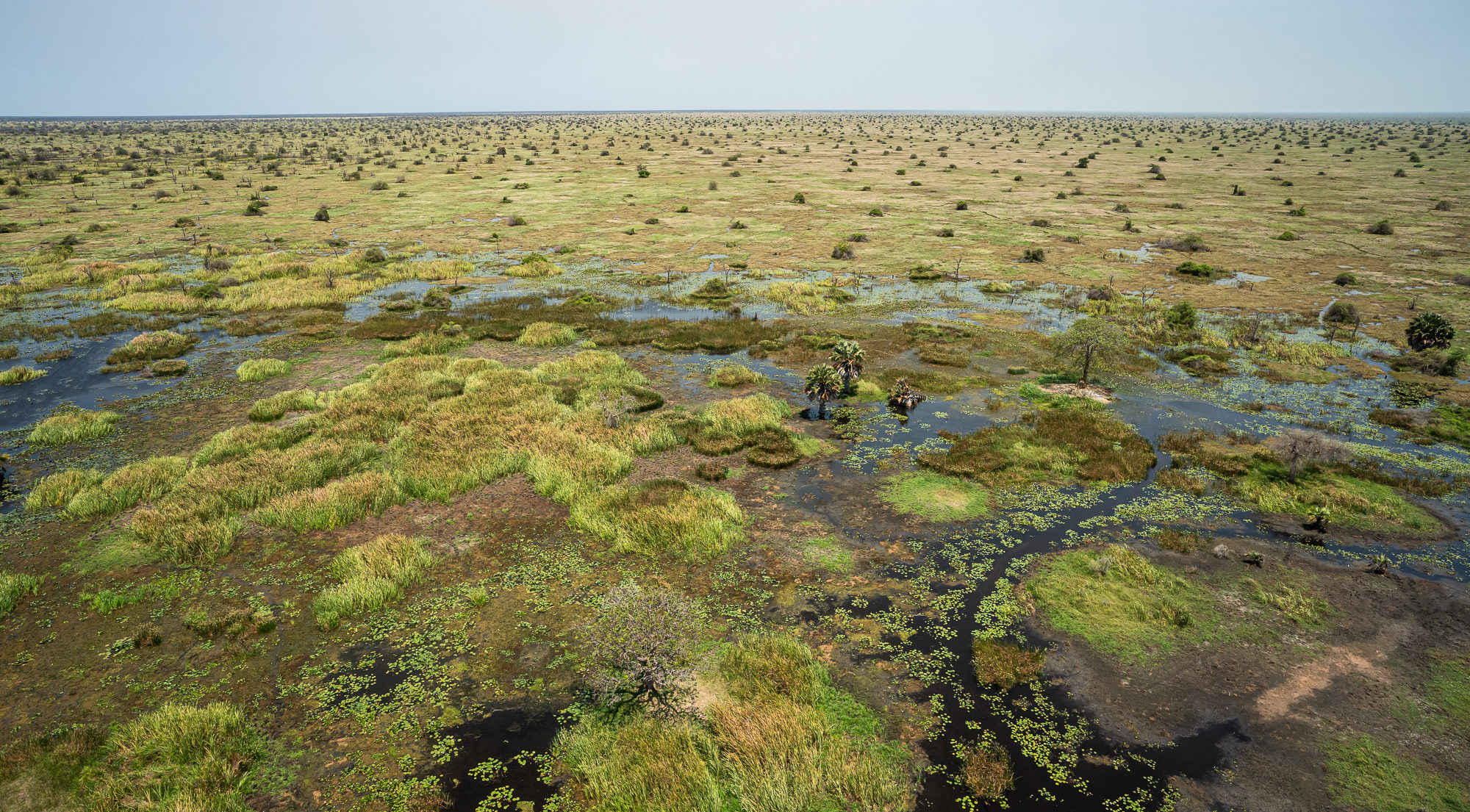

South Sudan possesses an abundance of water, which combines with its tropical climate, its sizable landmass, and its adjacency to the meeting of the Africa and Arabic tectonic plates to produce a variety of habitats. These include its vast and largely roadless savanna plains, the Sudd (the largest wetland in all of Africa), and the high-altitude forests found in its Afromontane region. It is home to the second largest mammal migration on the planet, that of the white-eared kob and the tiang, to remarkable numbers of shoebill, and a 10-15 million-strong population of mainly Nilotic peoples, with the Dinka and Nuer alone accounting for just under half of the population.

While over 60 indigenous languages are spoken in South Sudan, English remains its national language, a decision made when it achieved its independence in 2011. It seceded from its northern neighbour – North Sudan – after years of civil war, and went through another decade of civil unrest, before achieving relative stability in 2020. Unfortunately, memories of the wars and the alacrity with which the world focuses on any of its problems impact unfairly on the economy. As a result, South Sudan ranks as one of the least developed countries in the world, with its GDP per capita standing at just $1,070. The challenges are many, not least prospective plans to further exploit the country’s oil reserves in currently untouched lands.

Yet, with new beginnings also come new opportunities. Juba has shown encouraging signs of a willingness to protect the country’s unique natural habitats. A new partnership with African Parks will lead to the creation of a wildlife corridor between Boma and Bandingilo national parks, protecting 13 million hectares of wilderness in the process. The government has also noted the potential role of well-managed sustainable tourism in supporting these efforts. There has quite literally never been a more opportune moment to explore the wonders of this spectacular country, and in doing so, contribute towards the preservation of its extraordinary wildernesses.